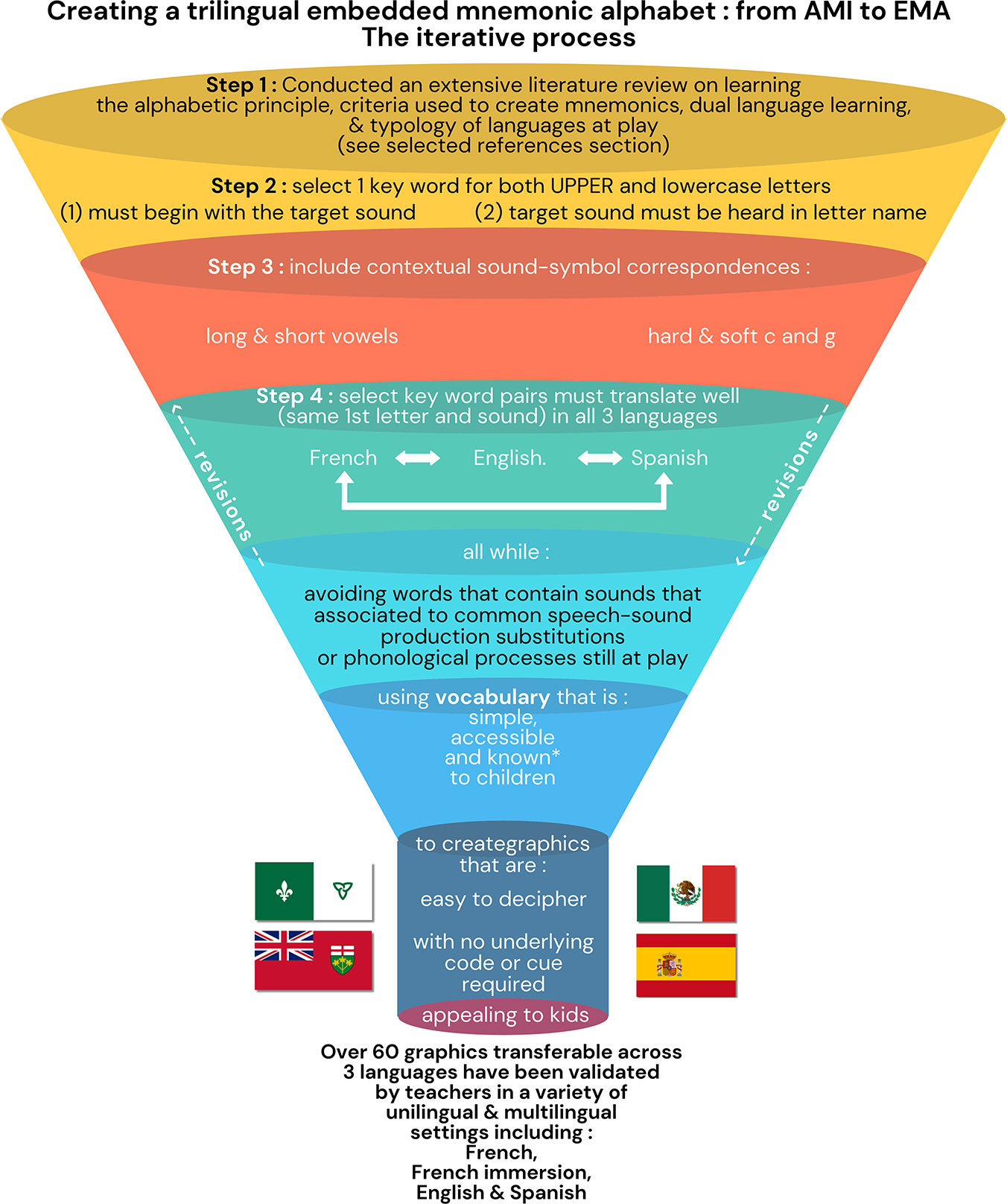

Creating an embedded mnemonic alphabet : An iterative process

Why use an Embedded mnemonic alphabet? One’s ability to write letters is closely linked to their knowledge of the alphabet letter names and the sounds they represent (phonemic awareness). Research has also shown that associating letter formation with letter sounds helps develop neural connections that support later reading skills (Golestanirad, Das, Schweizer, & Graham, 2015), hence the increase in popularity of « See it, say it, write it » activities. However, many preschool curriculums often neglect to integrate letter writing with letter sound instruction. Though the impact of first teaching capital versus lowercase letter formations has not been widely investigated as noted by Pence et al. (2010), studies indicate that the distinct shape of uppercase letters and their uniform placement (start : sky ; end : grass ; never on ground) makes them easier to learn than their lowercase equivalent, which include letters whose shape is identical – or nearly so – making it easier for children to confuse them (b/d/p/q ; u, n, h). That said, researchers agree that the greatest cause for confusion is less visual than auditory, and this is but one of many criteria to consider when assessing children’s written language skills. Letter reversals are common and are generally less frequent in students beyond grade 2.

How is an embedded mnemonic alphabet helpful? An embedded mnemonic alphabet has been proven to be highly beneficial, leveraging the strong correlation between learners’ knowledge of the alphabet (letter name), their phonemic awareness skills (letter sound) and their ability to write the letters (gross motor movement helps commit that shape to memory). By associating letter shapes with their corresponding sounds, this approach helps to develop neural pathways that are crucial for reading proficiency, as demonstrated by Golestanirad, Das, Schweizer, and Graham (2015), as well as writing (encoding and developing writing fluency). The documented benefits of pairing phonemic awareness with writing activities further highlight the effectiveness of this method, illustrating how it enhances cognitive connections and supports overall literacy development.

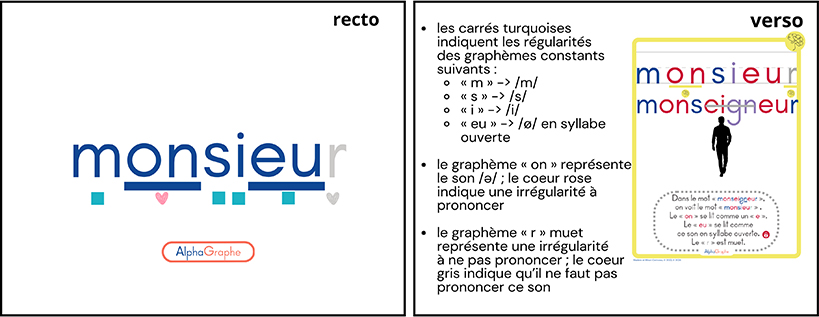

For a more comprehensive and extensive rationale for our key word selection and designing of individual graphics, please refer to AlphaGraphe (Minor-Corriveau & Madore, 2023).

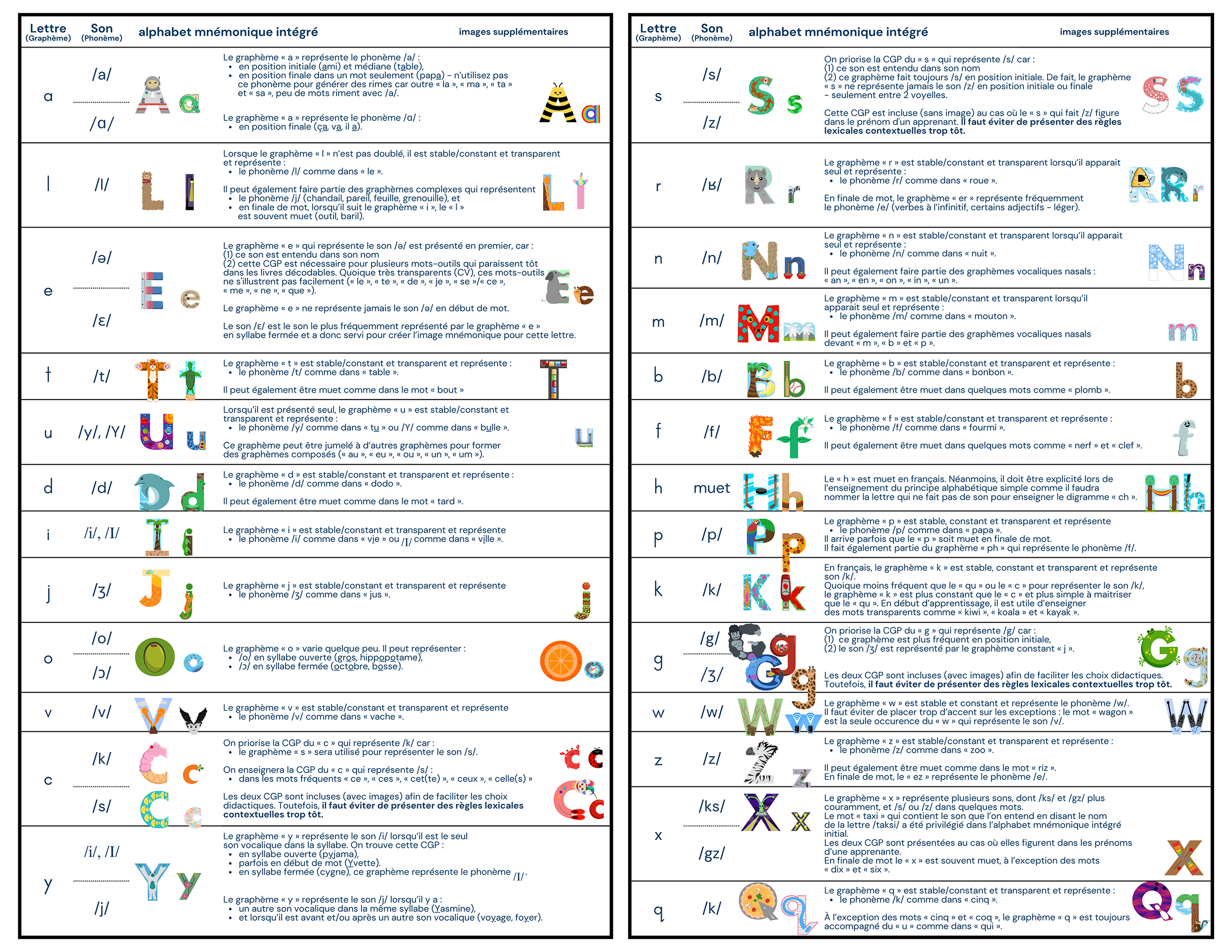

Criteria of an embedded mnemonic alphabet (Ehri, 2020 ; Massengil & Sundberg, 2008)

In a perfect world, mnemonic graphics created to represent letter-sound combinations should :

- start with the sound most often associated to the letter,

- letter shape must be clearly visible within the mnemonic graphic,

- lead to a quick association of the word and its 1st sound (object must be depicted in a transparent manner ; it should not require interpretation, additional story or hint in order to decipher what the image represent/means),

- refer to vocabulary familiar to children.

In addition to these basic criteria, we :

- focused on letter shape and avoided adding unnecessary detail in or extending around or outside the letter’s shape,

- added mnemonics for both upper and lowercase letters,

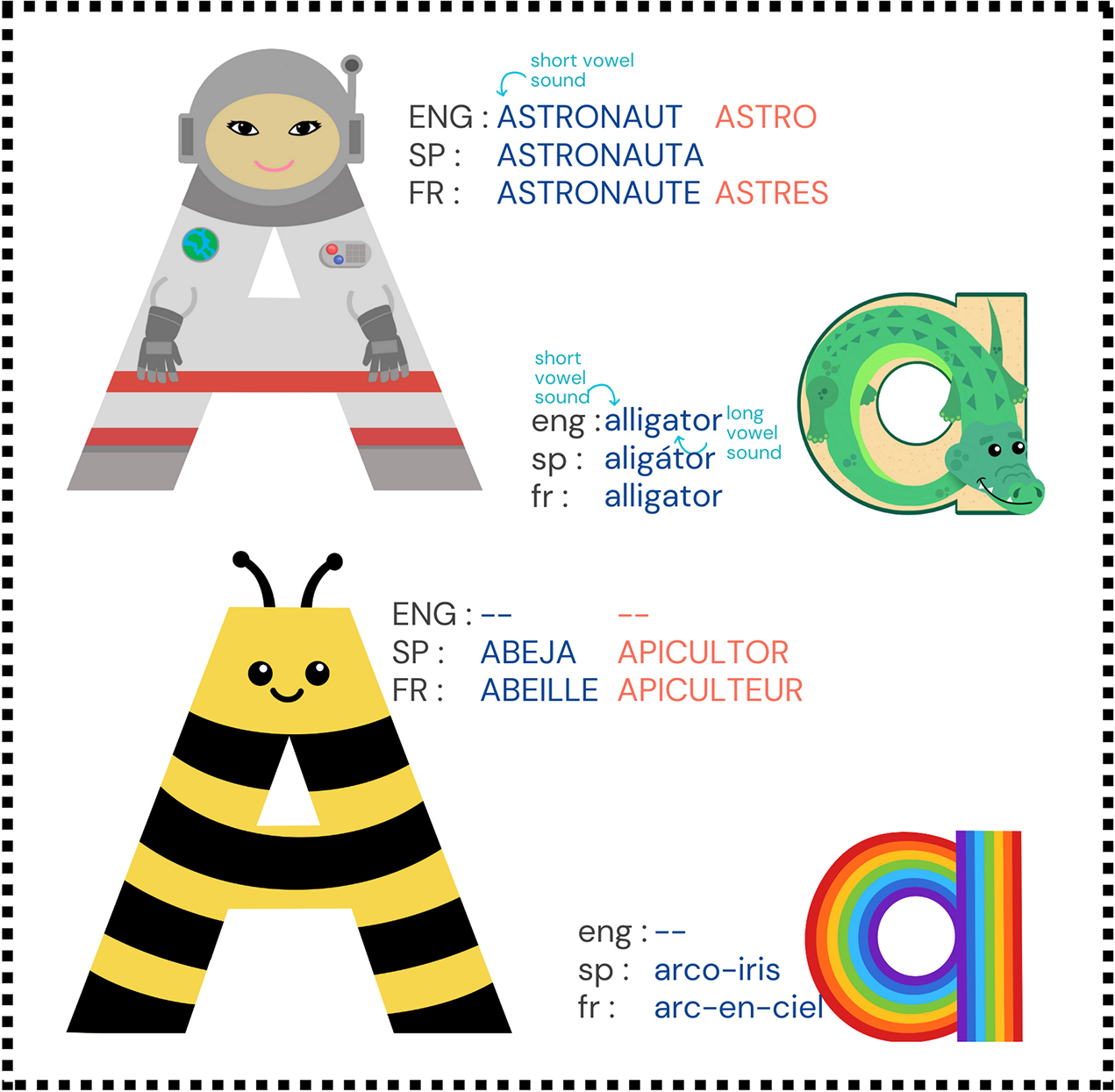

- maximized opportunities for translanguage by ensuring that all target words are transferable to the basic alphabetic principles in 3 languages : French, English & Spanish.

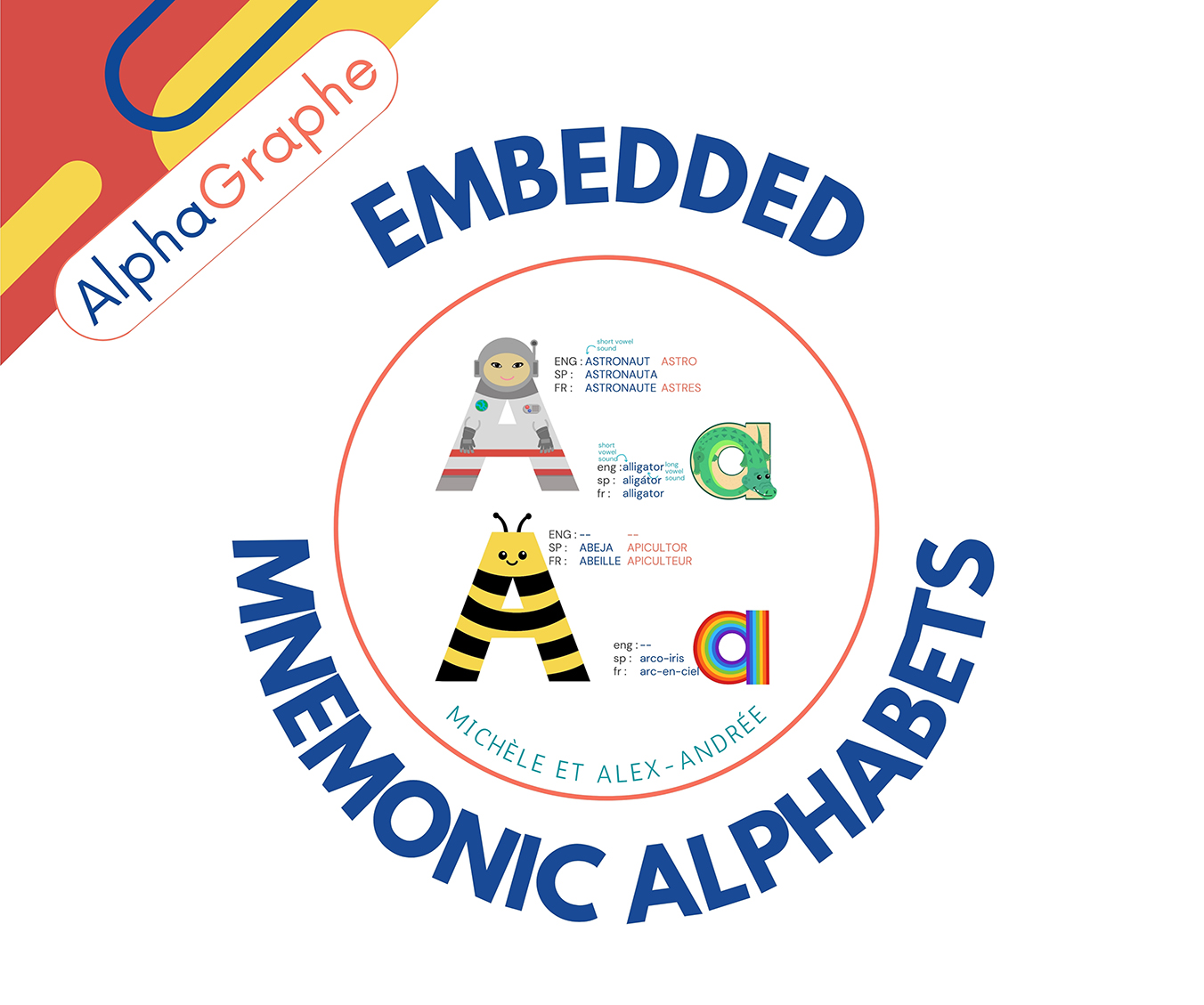

Various editions of these embedded mnemonic alphabets (EMA) have now been created. Each can be used in the following linguistic settings and some letter-sound mnemonics contain multiple graphics from which to choose:

- as a stand alone resource in each language

- French-English

- French-Spanish

- English-Spanish

- French-English-Spanish

This research-informed blog unpacks the questions and considerations that guided us through this iterative process that is ever evolving to accomodate different instructional contexts and realities.

We hope you find the information presented useful and we thank you for taking children’s literacy to heart.

Why include embedded mnemonics graphics for both upper and lower case letters?

Why not create only lowercase letters ? After all, they are 97 % more frequent that their uppercase peers. The common belief that having fewer mnemonics makes them easier to remember is actually the opposite. When researching what renders a mnemonic most helpful, it became apparent that for most upper and lowercase pairs, the graphic used for different graphemes would lose its mnemonic power because the end result would not be easily recognized by children.

Given the importance that a child places on their name, uppercase letters are required for capitalization of proper names – including their own – as well as at the beginning of sentences (which will come a little later but will indicate the beginning of sentences when reading even the most highly decodable book).

Doesn’t having more symbols (one for each letter, for each case) make learning the alphabet more difficult for young learners?

On the contrary : different graphic representations, namely – the following letter pairs

Aa, Bb, Dd, Ee, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Ll, Nn, Qq, Rr

all require letter shapes that are quite different when moving from upper to lower case.

A graphic using only one key word does not lend itself well to being represented by such different shapes. Having a different mnemonic graphic representation for each of these upper and lower case pairs serves to provide a visual cue that recalls the shape as well as the placement of the letters whether the letter shape pairs are visually similar, or different. This is also proof that having a greater number of distinct symbols (uppercase) is not more difficult to remember than having fewer symbols that are similar but not quite identical : lowercase b, d, p, q, anyone?

Fun fact : Did you know that the distinct shape of uppercase letters make them easier for children to remember ? True story. And they letters are less likely to be reversed since there are no uppercase letters that can be mirrored to reflect a different letter-sound correspondence. According to Treiman, Kessler, & Pollo (2022) letter shape can be a source of confusion when learning the alphabetic principle. Though lowercase letters are 97% more frequent than uppercase letters, studies have shown that children correctly identify and reproduce uppercase letters earlier and more reliably than their lowercase counterparts. Though there are few studies on the consequence of teaching upper or lower case letter formations first (Pence et al., 2010), we decided to include both cases and allow educators the freedom to decide when to teach which case.

Our decision to include both upper and lower case graphics considered these contributions to research and affords teachers the flexibility of focusing on lower OR upper case only, should they choose to do so. This also provides a variety of options for each letter, which in turn helps with explicit teaching of short & long vowel sounds during phonemic awareness activities.

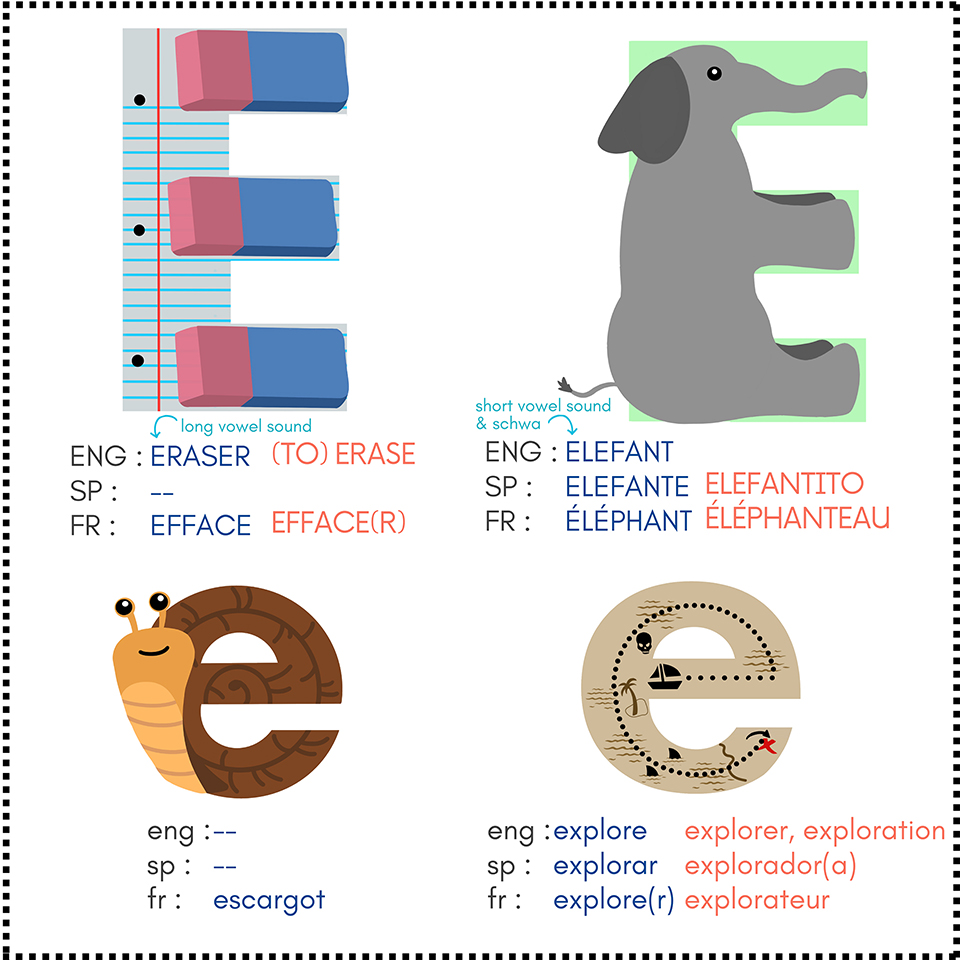

Consider the following scenario : how different would the « eraser » used to represent the uppercase « E » look if the same key word was also used to draw a mnemonic image for the lowercase letter ? While we’re at it, let’s consider another scenario, this time involving similar letters. When teaching handwriting and correct letter positioning, would the positioning of the uppercase « P » and lowercase « p » be as useful if they were represented by the same object ? Having different graphics indicates that the uppercase P (parrot) must be drawn from sky to grass , while the lowercase p (pizza) extends from grass to ground. Mnemonics are all about visual representation and in this case, associating a sound to a letter that looks like the key word that represents it.

Out of 26 upper/lowercase pairs, the following 8 are the only pairs whose graphic representation is identical but slightly smaller. In the case of these mnemonics, one could reduce their size and render them useful, regardless of case.

Cc, Oo, Ss, Uu, Vv, Ww, Xx, Zz

The following 6 pairs are similar in shape, though not identical, and the placement must be altered for two of them if their execution is to be deemed adequate :

Ff, Kk, Mm, Pp, Tt, Yy

The remaining pairs—just shy of half the alphabet—have such distinct upper or lower case shapes that their mnemonic value will be diminished due to their visual representations being altered in such a way that the upper or lowercase version is too far removed from the intended object.

Aa, Bb, Dd, Ee, Gg, Hh, Ii, Jj, Ll, Nn, Qq, Rr

For a mnemonic cue to be useful, the image must be transparent : when referring to these embedded mnemonic alphabet letters, the key word should be easy to identify upon looking at the letter. The more it requires an explanation, the less useful it might be for young learners.

After all, we’re trying to teach the code, so let’s not layer it with an entirely different code to master – this would defeat the purpose and lead to greater confusion.

All EMA/AMI key words and graphic representations were validated by kids and their teachers before being launched into the universe.

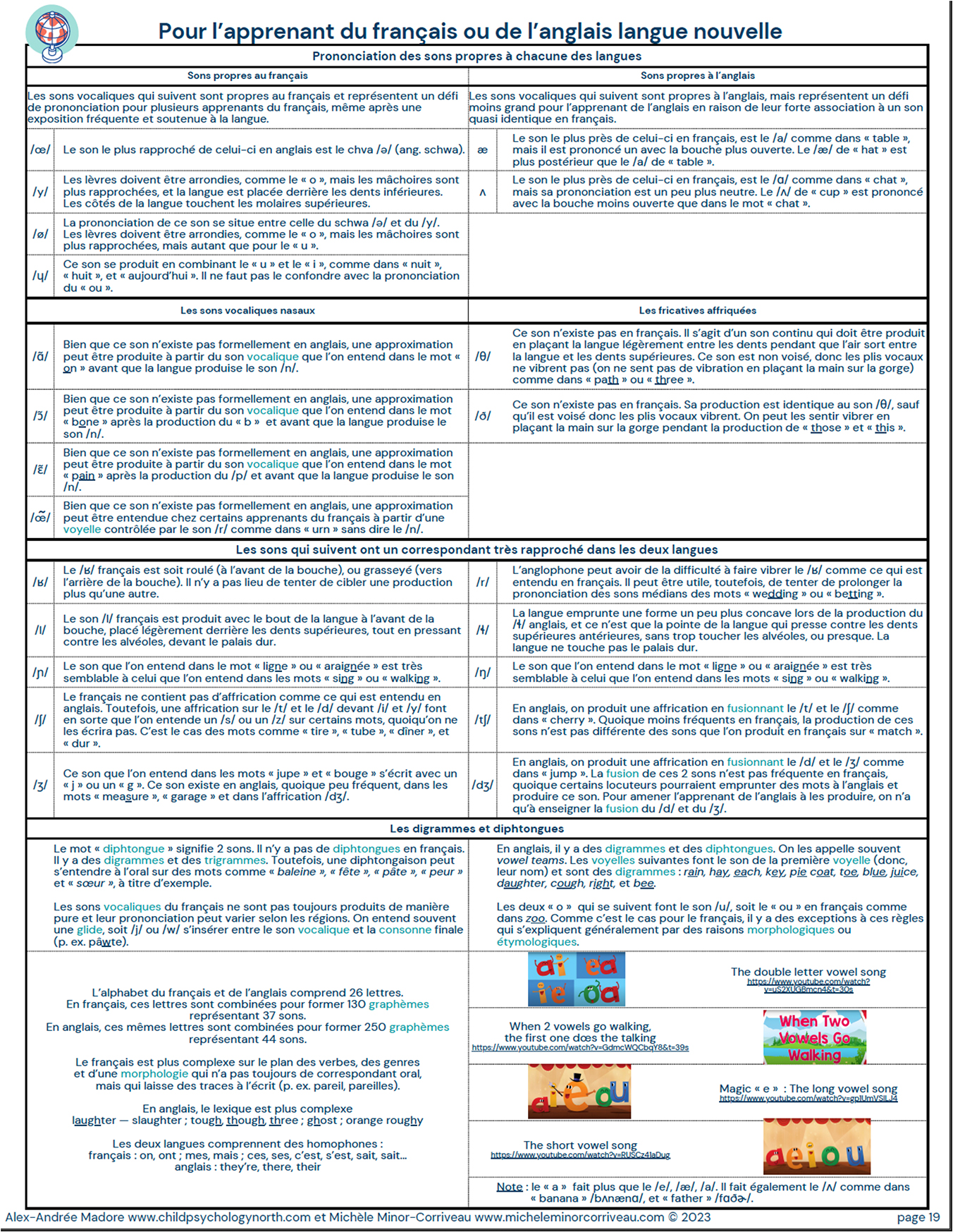

Using one embedded mnemonic alphabet across three languages as a springboard from L1 to L2 (or L3)

Beyond the age of six, learning additional languages requires making connections between the new languages being taught and those already learned (Paradis, Genesee, Crago, 2021). This process, known as cross-language transfer, involves applying knowledge from one language to another. For languages that share similar typologies, such as alphabetic / syllabic systems, using mnemonics that align with the same letter-sound combinations in other languages can alleviate the cognitive load for learners who are navigating two or three related though slightly different alphabetic principles. In practical terms, students in dual or multilanguage environments, such as those where French is the child’s first language as well as those who are learning French as an additional language, often face the challenge of acquiring a second or third language, even before they have not yet fully mastered the code associated to their first language. This also explains why, once children learn to read well enough in one of these alphabetic languages, they will venture out and try to apply their knowledge to the other, lesser known code. At times they will be successful, other times they will need redirection, but rarely do they need to start at square one in order to become fluent in their second or third language. We will refer to this as springboarding from one language to benefit learning another.

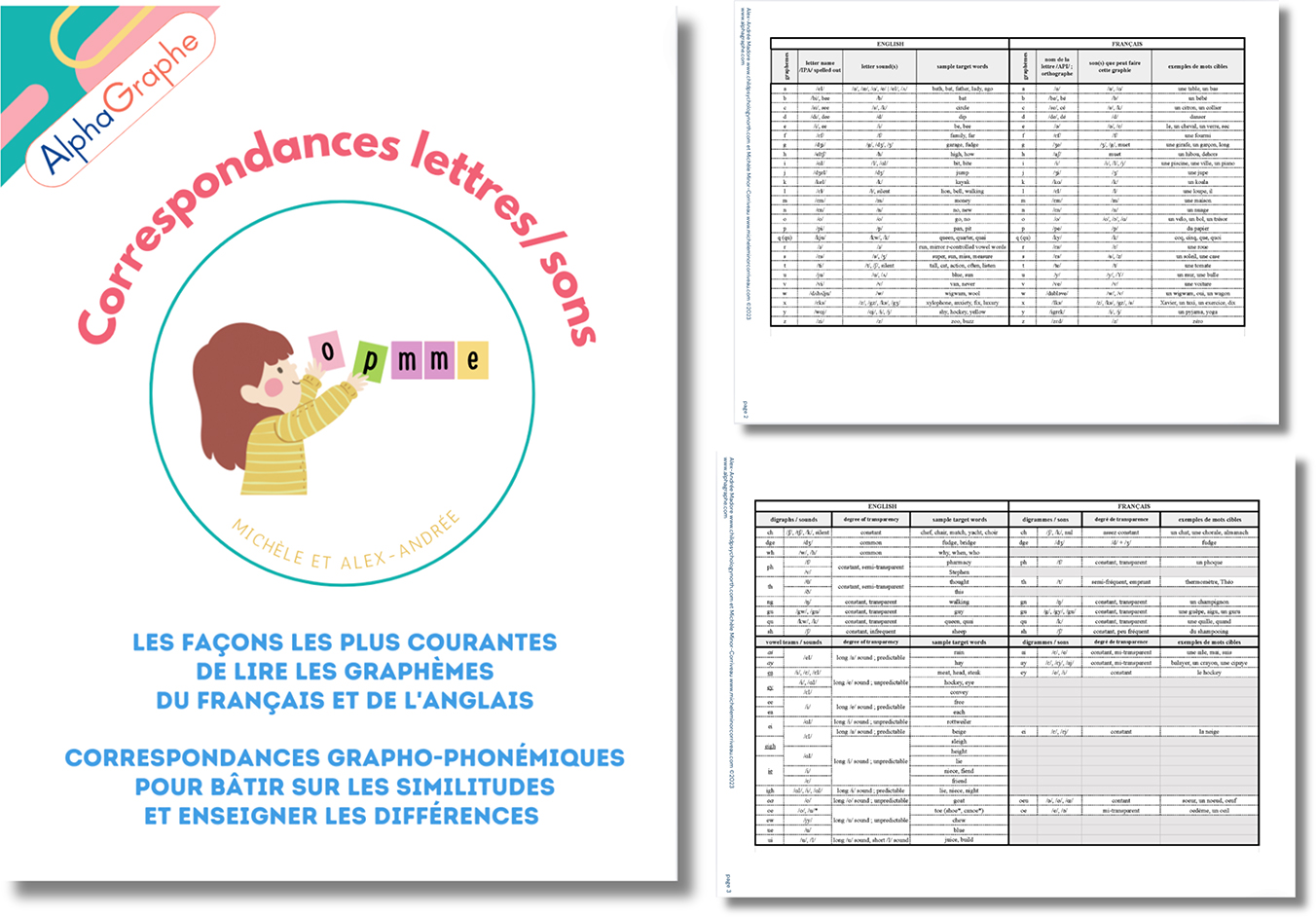

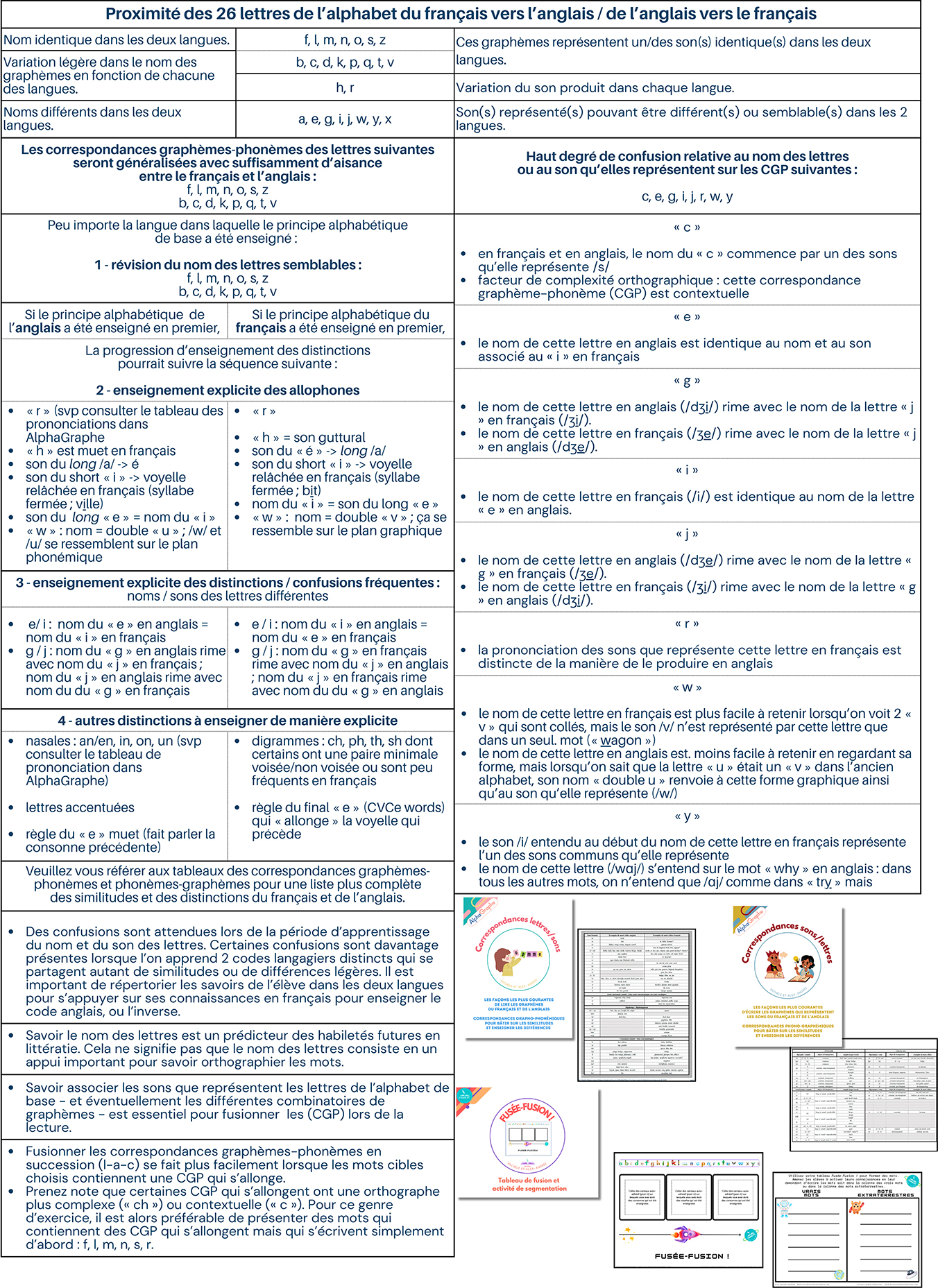

The best way to springboard from French to English or English to French is by reducing the amount of new information presented at once. If the English alphabetic principle has been taught first, then French can be introduced by reviewing the sound-symbol correspondences that are the most similar to the language that is already known or that has been mastered. Then, time should be spent highlighting what is different in both languages, and scaffolding instruction in such a way that the scope and sequence being followed still begins with what is most simple, eventually venturing toward what is more complex.

Criteria used to create a trilingual embedded mnemonic alphabet (EMA)

Why create an EMA? To provide teachers in multilingual settings an embedded mnemonic alphabet that helps students associate sounds to their symbols across 3 languages : French, English and Spanish.

Goal of an EMA: To help learners master letter sounds to their corresponding grapheme (shape).

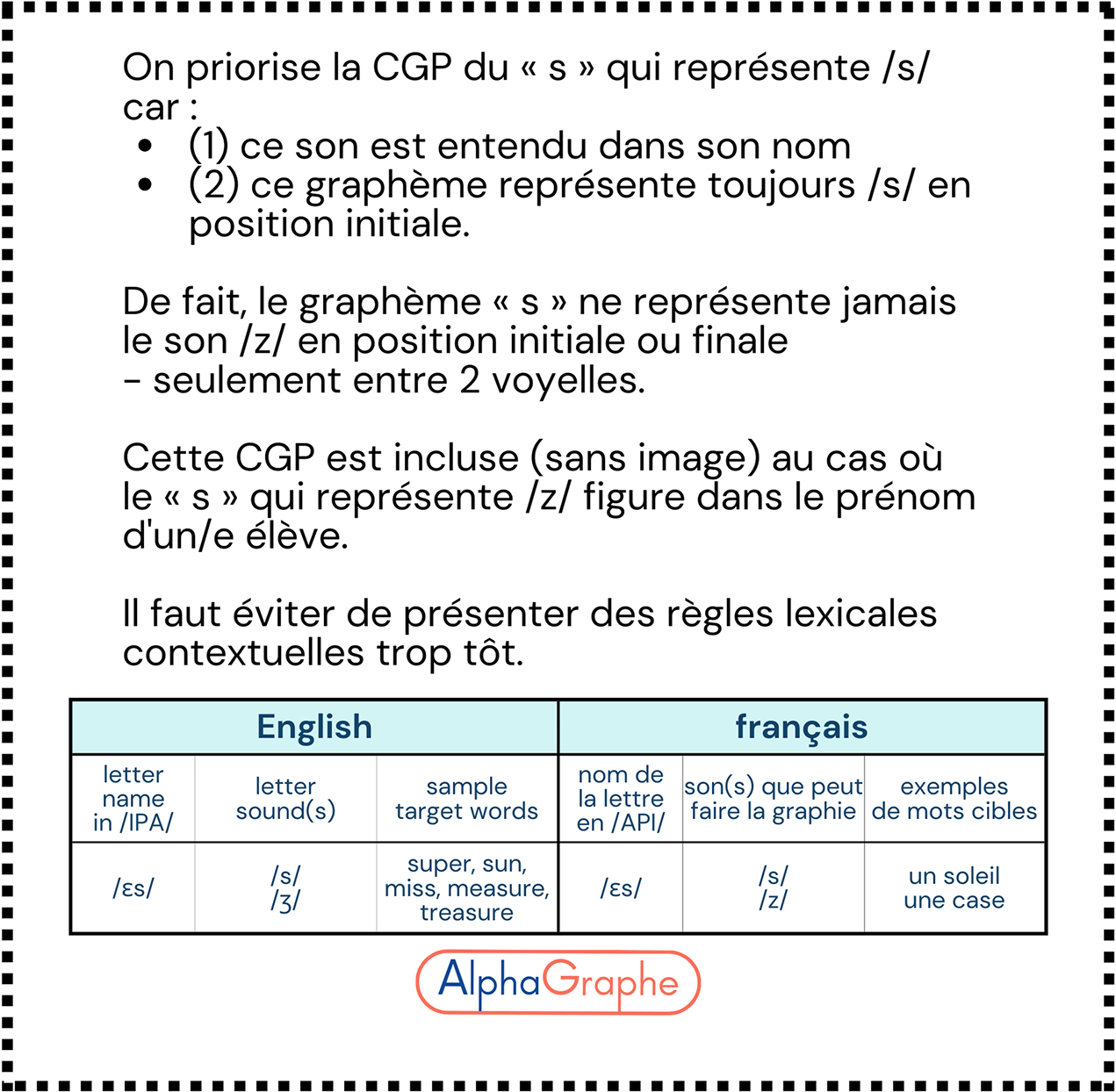

1 – Sound-symbol correspondance

Does the key word begin with the target sound most commonly associated to the grapheme represented? (phonemic awareness)

2 – Letter name / letter sound

When a grapheme can be used to represent multiple sounds, can the sound represented also be heard in its name whenever possible ?

3 – Vocabulary

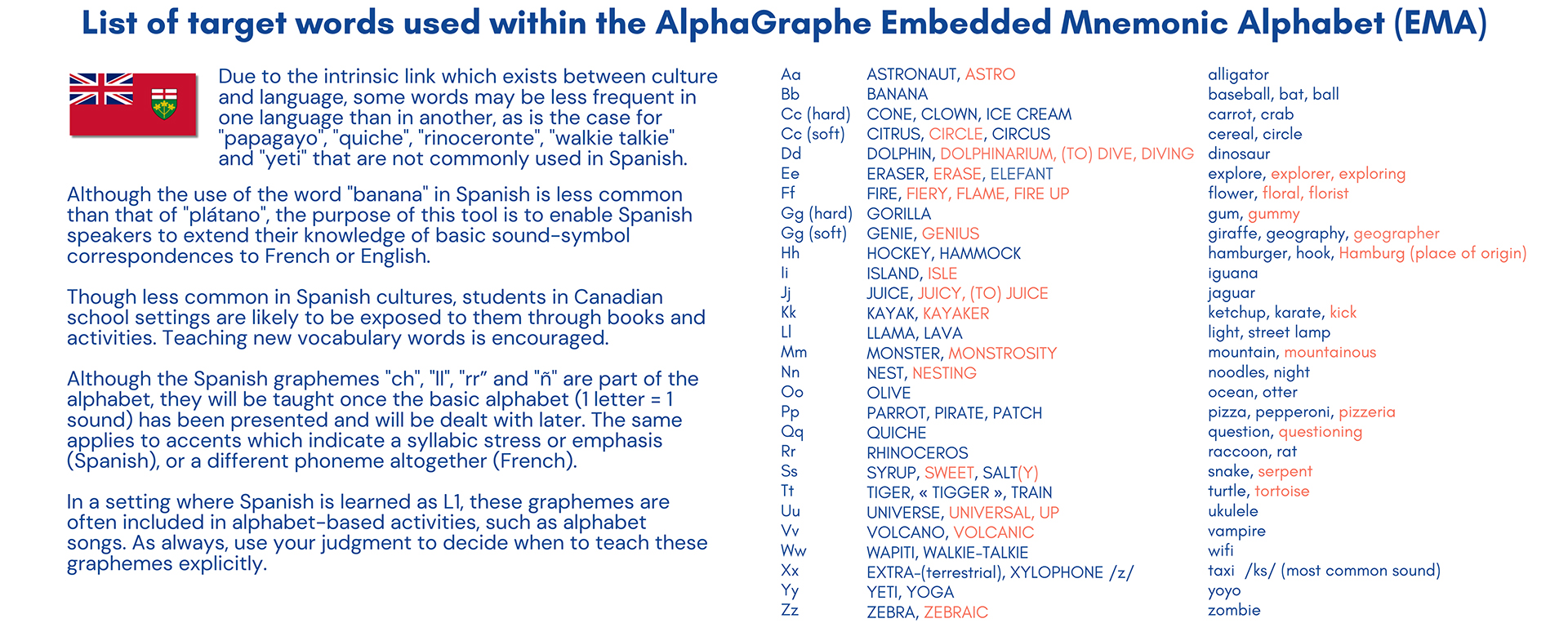

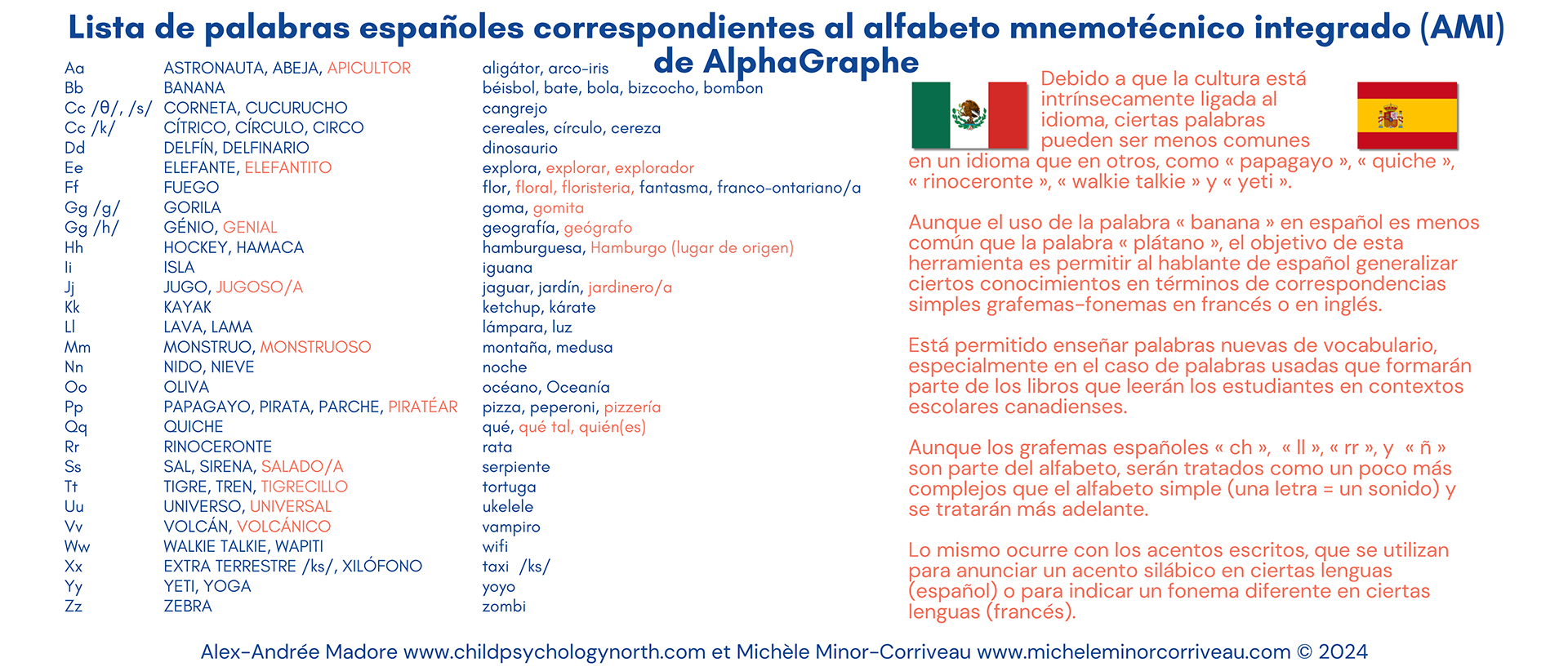

The key word should be as familiar as possible to young learners. When creating a trilingual EMA, the key word selected might be more common in one language than another. Whenever possible, we opted for words that are known to children. The following words might be less common in some cultures but are likely to be found in children’s books and teaching units : papagayo (parrot), quiche, rinoceronte (rhinoceros), and walkie talkie. These could require explicit vocabulary instruction, which is encouraged through read alouds before any language-based activity, either oral or written.

4 – Articulation / Phonological processes

From a speech production perspective, we avoided words that might contain sounds that are still developing among children. These include :

- avoiding words which contain the /r/ + /o/ (i.e. roll) or /r/ + /w/ (i.e. warm) sounds, as gliding is still quite common at this stage – though blends can lead to slight affrication in English, students will need to learn to isolate these sounds in order to encode them accurately;

- leaving in a few blends, while providing a non-blend option affords teachers added flexibility with respect to instructional decisions.

5 – Graphics

Let’s face it : how the objects found in our environment look has little or nothing to do with the shape of the first letter in the word used to name them. Creativity was paramount : we strived to create graphic representations that depict the letters in a way in which the key words could easily be recognized by students. No guessing, and no extraneous detail should be required to access the key word.

In keeping with our purpose of providing a teaching tool in which the sound/symbol correspondence would be consistent across three languages, the following criteria was used to guide our decision-making.

6 – Translanguaging

Key words selected must contain sound/symbol correspondence consistent across three languages : French, English and Spanish.

Though the key words do not have to be identical in all three languages, they do require the same initial sound.

Regional speech-sound production, dialect and linguistic variation as well as cultural sensitivity was top of mind in selecting the key words and creating their graphic representation.

Challenges, Compromises & Solutions

In an effort to avoid a particular challenge that one key word might present in one language, a different set of challenges might occur in other languages ; whenever this occurs, teachers now have options to choose from to better reflect the regional dialect or linguistic variation of students in their area.

Added value of AlphaGraphe’s AMI/EMA

To date, no other embedded mnemonic alphabet has included :

- different graphics for each uppercase and lowercase letters

- different graphics for both hard and soft « c » and « g »

- crossover between as many languages

Which of the AMI/EMA letters required some degree of flexibility with respect to one or some of these criteria? What was the solution / compromise? Here are some of the challenges we faced along the way, and how we chose to solve them, making AMI/EMA graphics fully functional mnemonics that can be used in monolingual settings and inclusive multilanguage settings.

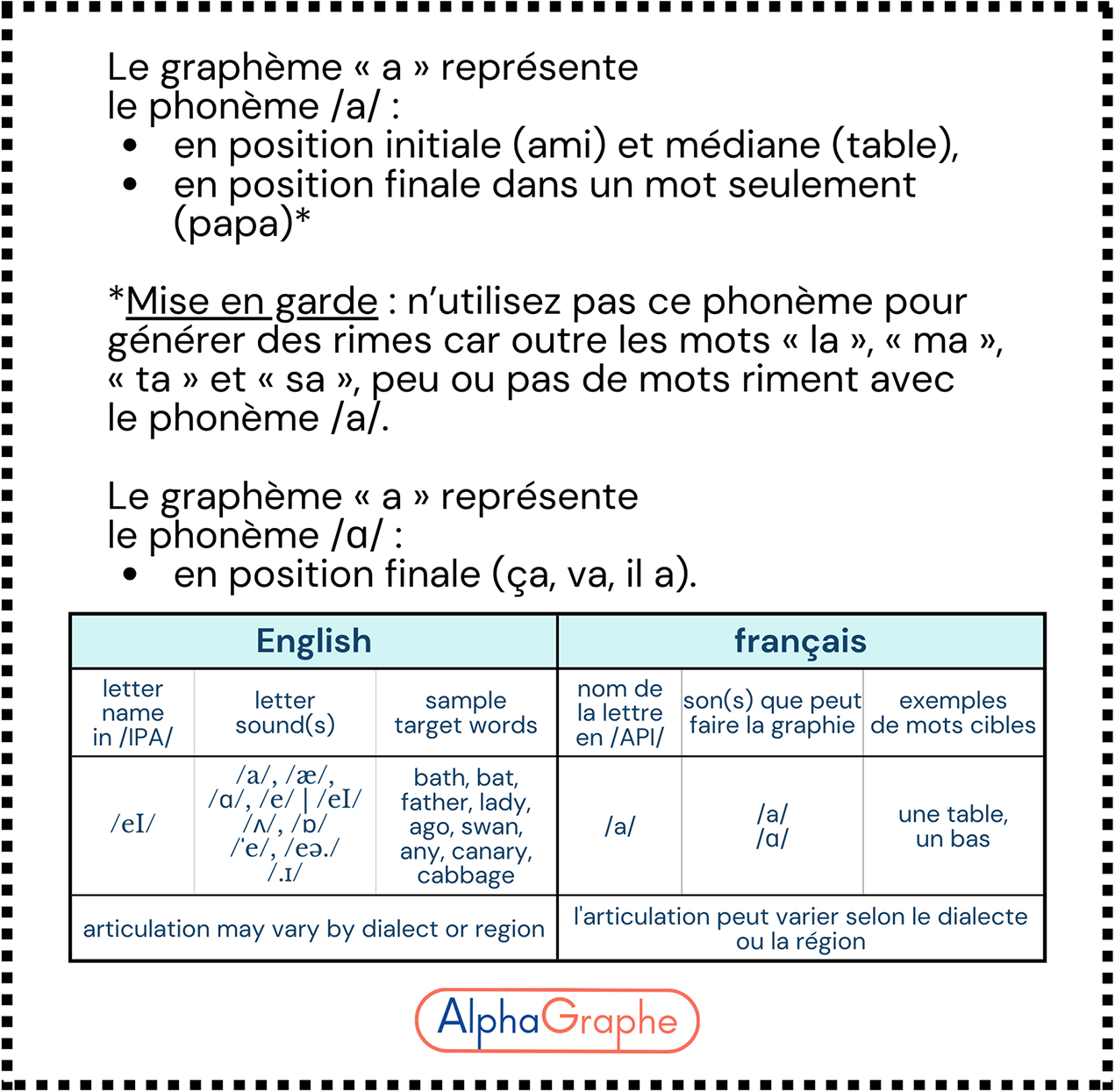

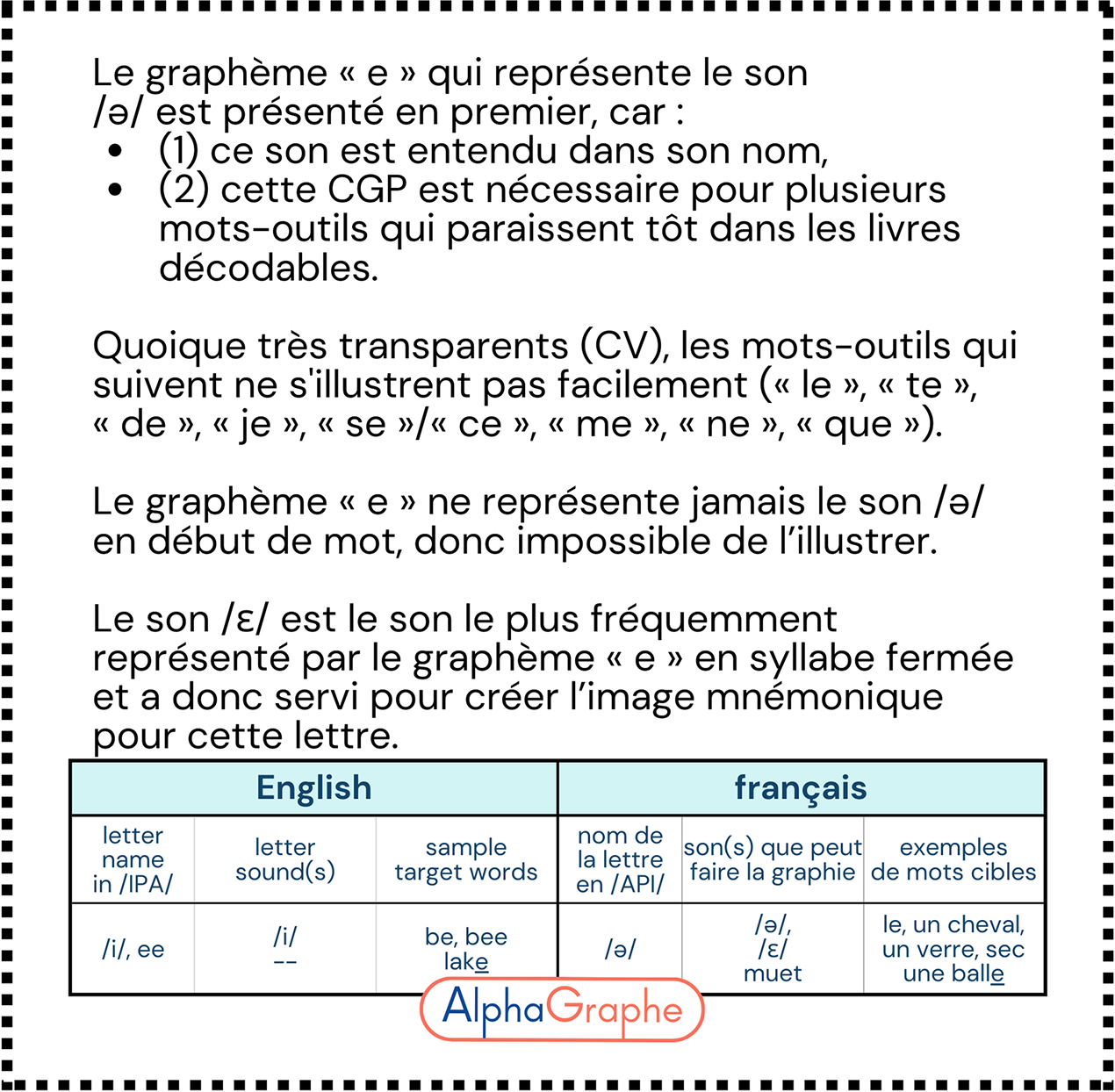

FRENCH

The sound heard in the letter « E »’s name never occurs at the beginning of the word. When the /ə/ sound is heard, the syllable is open in monosyllable function words like « de, me, je, le… » which cannot be drawn or « cheval » which does not start with that letter.

Solution : To be consistent with the design criteria, we opted to represent this letter by using a key word that starts with /ɛ/, the short vowel sound in English, and also coincides with the sound this letter most often represents in French & Spanish.

ENGLISH

Consonant clusters (blends) : r- and l-blends seem to be more impacted by coarticulation in English than in French or Spanish. The slight affrication that can be heard on English words that contain blends like « train » or « dream » is heard in French on words like « tigre » and « diner » but not on words that contain r- or l- blends. These sounds seem easier to isolate in French and Spanish.

solution : if you wish to avoid blends in English, you can substitute :

- carrot for clown/crab

- fire* for flower

- salt* or syrup* for snake

- tiger for train

*Letters whose upper and lowercase representation is identical (or nearly so) can easily be modified to migrate from upper to lower case for added flexibility

Cc, Oo, Ss, Uu, Vv, Ww, Xx, Zz

Ff, Kk, Mm, Pp, Tt, Yy

Download the request form to access the high resolution png AMI/EMA graphics here.

Why not use « qu » ?

In English « qu » always represents 2 sounds : /k/ + /w/. When teaching the alphabetic principle, these 2 graphemes are often paired together in alphabet activities. Even though they most often occur in succession, these graphemes also exist on their own, therefore children should learn each letter’s name and its corresponding sound. They should also learn to isolate these sounds individually during phonemic awareness activities.

solution : if it is important to represent the commonly heard /kw/, use the lowercase graphic for « question »

long/short vowels : wherever possible, long and short vowel sounds are both represented by an upper or lowercase vowel in English:

short vowels :

- a : ASTRONAUT, alligator

- e : elephant, explore

- i : iguana

- o : otter, OLIVE

- u : ukulele*

long vowels :

- a : alligator*

- e : ERASER

- i : ISLAND

- o : ocean

- u : UNIVERSE, ukulele

- y : YETI, yoyo = glides as the long /i/ represented by « y » is not common in initial position

*though not in initial position, these sound/symbol correspondences can be used to enhance phonemic awareness activities beyond the first letter. Key words have been included to represent words such as « up »

SPANISH

The Spanish written code is considered more transparent – closer to a 1:1 correspondence – than opaque languages such as French or English. To find key words deemed appropriate for use with latino learners in Canada, we consulted teachers whose first language is Spanish. Spanish is quite forgiving: for example, the two orthographies for the key word « ZEBRA » (i.e. « zebra » or « cebra ») can both be used.

Due to the intrinsic link which exists between culture and language, some words may appear less frequently in one language than in another, as is the case for “papagayo”, “quiche”, “rinoceronte”, and “walkie talkie”. Although the use of the word “banana” in Spanish is less common than that of “plátano”, the purpose of this tool is to enable Spanish speakers to extend their knowledge of basic sound-symbol correspondences to French or English.

solution : Though less common in Spanish cultures, students in Canadian school settings are likely to be exposed to them through books and activities. Teaching new vocabulary words is encouraged and permitted. Just as one would be expected to do for any read-aloud or book-related activity, explicit teaching of less common vocabulary words is essential and will help enrich vocabulary skills while teaching the alphabetic principle.

The freedom to make well-informed instructional decisions

No resource can target all goals at once. Using an embedded mnemonic alphabet can be a powerful tool when integrated into an explicit, systematic, structured, progressive and cumulative literacy block. Your phonemic awareness tasks will need to include words other than those found in the AMI/EMA graphics.

Every embedded mnemonic alphabet system has had to make creative decisions during the design process. Slightly bending some rules with respect to one letter-sound combination to be consistent with research is not likely to have adverse effects on a child’s learning : in contrast, not following ANY set of research informed rules might. On a few occasions, our criteria benefitted from a little leniency, especially when:

- sounds do not occur in initial position, as is the case for the letter « e » in French, and

- ideal words could not be visually represented to reflect a concrete object that children would recognize easily.

These are not deal-breakers : they are informed instructional decisions.

For the deep divers

Use of multisyllabic words

AlphaGraphe’s EMA was designed to be integrated into an explicit structured systematic instruction activity at the tier 1 level. Words that were deemed to be known and meaningful to children or those who were thought to bring interest to an explicit vocabulary instruction lesson were prioritized. These words are not restricted to monosyllabic types for the following reasons :

- though monosyllabic CVC words are abundant in English, this is not so for other languages such as French or Spanish,

- all English monolingual mnemonic alphabets include some multisyllabic words.

The purpose of such a tool is NOT to replace a universal screening measure, but including multisyllabic words can serve as a red flag for those students who have difficulty repeating multisyllabic words despite being frequently exposed to them. These students could prove to be at risk for written language disorders ; if you are concerned with their ability to repeat multisyllabic words – be they nonsense or meaningful words – please consult your educational SLP as soon as possible.

Spanish and French speaking children eliminate this phonological process earlier than English speaking children (around 3 years for French and Spanish ; 4 years for English speaking children). By the age of 5, weak or unstressed syllable deletion is generally eliminated. If you are unsure if the speech-sound patterns your students are demonstrating are typical for their age, please contact your educational SLP. Speech-sound disorders are common among weak readers and children with dyslexia.

Co-articulation and common speech-sound substitutions

The term « gliding » is used to describes a common phonological process whereby children substitute glides (also referred to as semi-consonant or semi-vowels) for liquid sounds, such as /r/ and /l/. This speech sound pattern is especially present in words that contain both glides (/w/, /j/) and liquids (/r/, /l/) (« worry ») as well as words in which the /o/ or /u/ sounds are in close proximity to /r/ and /l/, such as « ruler » and « road ». Upon school entry, it is still quite common for students to continue to produce gliding. When selecting target words for letters whose correspondant was /l/ or /r/, we avoided using words which contained the sounds for which liquids are most often substituted or sounds that would lend themselves well to this process when in close proximity. Other examples of such words are : « roll », « warm » or « yellow »).

In English, affrication can be heard in words that contain a consonant blend involving the sound /r/ at the beginning of words. For example, a child might tell you that they hear the /tch/ sound in the word « train » or the /dge/ sound in the word « drain ».

In French, the same phenomenon occurs, though not with blends which are more easily isolated than in English. This happens in words that contain the /t/ or /d/sounds followed by the /i/ or /y/ sounds (tigre, petit, dinosaure, dur). Children might say that they hear a /s/ or /z/ sound between the consonant and vowel (tsigre, dzinosaure). They are not mistaken. It is important to acknowledge what they have heard, and highlight the slight discrepancies between oral language and its written form.

This is the sign of heightened phonemic awareness skill and is the goal ! Students who notice that sometimes they hear a « ch » or « dge » sound in « r » blends that involve « t » and « d » have in fact exceeded expectations. Their phonemic awareness skills have become quite precise. In French, the same is true of students who notice that there is a « s » after the « t » when francophones would say the word « tigre » : it actually sounds like « tsigre ».

Once again, the word « train » is useful when springboarding from English to French because students will need to isolate these sounds in more complex syllable structures since vowels are not as easily influenced or controlled by « r » in French.

/r/ colouring

Some /r/ colouring can be heard on vowels in words such as « orange ». Use « olive » if you prefer. In a French immersion setting, the word « orange » is useful for isolating the vowel from the /r/ precisely because of its position : it is not always easy to do so in medial or final position and is a necessary step to teaching the pronunciation of sounds that vary between similar languages.

Cluster reduction, a naturally occurring phonological process when children acquire language is generally resolved before school entry or during the first year thereafter (English : 4 yrs ; Spanish : 5 yrs). Though preference was given to words that contained single consonants wherever possible, some words that could be used across all 3 languages were included despite containing consonant clusters (blends). Once again, since this phonological process should be resolved within the first year of school, having a few key words that contain consonant blends might help identify the learners who might benefit from a consultation with your Speech-Language Pathologist. For added instructional flexibility you may wish to use the key words « cone », « carrot », « syrup » and « tiger » if you prefer avoiding consonant clusters in initial position.

Dual language learners

When teaching dual or multi language learners, please keep in mind that children who are learning two or more distinct languages, each with its own predictable speech-sound patterns, may exhibit some of these patterns in their non dominant language(s) longer than their monolingual peers. When in doubt, check it out ! Consult your educational SLP if you have questions pertaining to the speech (articulation, motor skills) or language (understanding, vocabulary) development of your students.

Low-frequency graphemes

Finding words that are easy to represent, using a target word that can be depicted to resemble the shape of the letter without the students having to guess what the letter might represent is quite the challenge. This is true of all graphemes. This is especially true when the words containing low frequency graphemes are not very common. The real feat was to find a word that would be common across English, French and Spanish, all while beginning with the same letter-sound combination in each language.

In English and French, the letter « x » represents many sounds. Both languages have but a few words that begin with the letter « x », so the pool of vocabulary words known to children at this stage is quite shallow. In Spanish, this same letter represents different sounds than those represented in French and English.

Despite its overuse, the word « xylophone » is certainly an adequate word to use when teaching this sound-symbol correspondence. The « x » represents the /ks/ sound more often than it does the /z/ sound, though rarely in initial position. To this end, the words « taxi » and « extraterrestrial » have been added to the roster even if the letter « x » is not in initial position.

Why not use « qu »?

One resource cannot be all things at once. The word « quiche » has been borrowed from French and is listed as a favourite menu item the world over, including restaurants whose menus are available in English. In fact, the « qu » in English represents 2 sounds : /kw/. Since the purpose of an embedded mnemonic alphabet is to help children learn to associate the most common sound – ok in some cases, 2 sounds – to its corresponding symbol, we intentionally left out digraphs, vowel teams. We have another tool for that, and it can be downloaded here : Napperon et AlphAffiches des graphèmes composés, complexes et contextuels.

Even though the letter « q » is seldom seen without its partner « u » in English, « q » still represents /k/ while « u » represents /w/ in most words except those that are not borrowed from French (« quiche ») or in proper names such as « Qatar ». Quite recently (August 29, 2024), a news story indicated that kids were being sent to « qamp » and omitted the « u » to pronounce this word the same way as « camp » would be spoken (see « Summer Qamp » documentary on building trust with LGBTQ2S+ teens by filmmaker Jen Markowitz)

Long & short vowels : where to begin?

Some scope & sequence programs favour short vowels while alternate between long and short vowels. As is the case with certain basic concepts in opposition, when it comes to sound-symbol correspondence, we must often teach these skills in opposition. For example, when teaching the basic concepts same/different and big/small, we must teach both together. This is also true of categories. When teaching phonemic awareness, we must also be mindful of the linguistic properties of the sound-symbol correspondences we are targeting. Minimal pairs are used to teach the difference in voicing for sounds such as « f » and » v ». Wherever possible, when creating AlphaGraphe’s EMA, a graphic representing both long and short vowels was used either on the upper or lowercase letters.

In English, the words « universe » and « ukulele » begin with a glide (/ju/-/k/-/ə/-/ɬ/-/ej/-/ɬ/-/i/). This slightly hidden /j/ sound shifts the vowel sound. The keyword « universe » has a nasal variant where /n/ alters the short /u/ sound slightly. An easy way to adjust this keyword is to have students point « up » at the universe as they say the first sound. In French and in English, words that share a sound represented by the letter « u » that are known to children at this stage are few and far between. We opted for the best alternative.

Remember : the ultimate goal of an embedded alphabet is to create an association between the letters (graphic shape) and the sound(s) they often represent. Teachers must exercise their right to make instructional adjustments as long as they fall in line with the current best pedagogical practices.

Looking for more resources?

AlphaGraphe’s scope and sequence pertains to the French code and has first and foremost considered orthographic complexity and consistency. There are many fantastic scopes & sequences to follow for teaching English*. Please refer to your favorite S & S to learn more about the sound-symbol correspondences (SSC) found in English. This « teacher’s code pack » reflects the linguistic properties of the SSC for the 26 letters of the alphabet as they pertain to learning French, therefore the descriptors and rationale of each mnemonic found on the reverse side card in this code pack are not available in English. To better understand the similarities and differences between English and French, please refer to the following document, also helpful if teaching in English only settings : Correspondances sons-lettres et lettres-sons. This comprehensive, though not exhaustive list of SSCs sorted by grapheme or by phoneme for both languages, is essential for all who are teaching students in French/English language settings.

The key words beside each mnemonic now indicate the language in which they can be used. The various editions of AlphaGraphe’s embedded mnemonic alphabet (EMA) allow you to customize your resources by using the key word graphic that best aligns with your instructional goals.

The spelling rules, exceptions and irregularities can all be found in the Napperon des graphèmes composés, complexes et contextuels and AlphaListes, a document that contains various wordlists that group words together by spelling pattern can be downloaded for free.

All AlphaGraphe code packs are sorted alphabetically for ease of reference. Simply refer to the scope & sequence of your choice to decide what to teach next. Don’t forget to check out our teacher’s code pack to uncover all you need to know to start teaching the alphabetic principle to learners in English, French or multilingual settings.

Keep in mind : When teaching two languages that rely on the same alphabet system such as French, English and Spanish, the scope & sequence for each language must be realigned to reflect what the student has been taught and what they might not have mastered. In theory, SSCs that have been mastered in L1 and have identical or nearly identical corresponding SSCs in L2, could be presented quickly and mastered with minimal effort. SSCs that follow a different set of spelling rules in both languages could create more confusion if they are presented before students have been able to master them in their L1. Not surprisingly, SSCs that are very different might be easier to master in one’s L2 in comparison to those that are much more closely linked to their L1.

Slant Systems has developed a high-quality research-aligned scope & sequence. Many others are available : the trick is always to teach spelling patterns while progressing from least to most complex, while teaching the « not yet decodable » high-frequency words and « heart-words » as the need arises.

In a nutshell, we tried to :

- use target words that depict tangible images, as abstract images or actions may not always create a meaningful image in a child’s mind, and

- avoid superfluous detail outside the letter shape ; if some detail appears outside the boundaries of the letter, we aimed to keep it low key, with the main focus being drawn to the letter shape itself.

More information on handwriting development coming up in :

A guide to articulation of speech-sounds foreign to source language can be found on page 9 in the « Documents d’appuis » section of AlphaGraphe.

References

Agramonte, V., & Belfiore, P. (2002). Using mnemonics to increase early literacy skills in urban kindergarten. Journal of Behavioral Education, 11(3), 181-190.

Baker, S.K., Santiago, R.T., Masser, J., Nelson, N.J., & Turtura, J. (2018). The Alphabetic Principle: From Phonological Awareness to Reading Words. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Improving Literacy. Retrieved from http://improvingliteracy.org (http://improvingliteracy.org).

Bellezza, F.S. (1987). Mnemonic Devices and Memory Schemas. In: McDaniel, M.A., Pressley, M. (eds) Imagery and Related Mnemonic Processes. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4676-3_2

Bowen, C. (2011). Table1: Intelligibility. Retrieved from http://www.speech-language-therapy.com/ https://www.speech-language-therapy.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=29:admin&catid=11:admin&Itemid=117

Brosseau-Lapré, F., Rvachew, S., MacLeod, A., Findlay, K., Bérubé, D. & Bernhardt, B. (2018). Une vue d’ensemble : les données probantes sur le développement phonologique des enfants francophones canadiens. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 42.

Deacon SH, Desrochers A, Levesque K. Learning to Read French. In: Verhoeven L, Perfetti C, eds. Learning to Read across Languages and Writing Systems. Cambridge University Press; 2017:211-242.

Ehri, L. C., (2020). The Science of Learning to Read Words: A Case for Systematic Phonics Instruction, Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1),pp. S45-S60. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq. 334

Ehri, L.C. (2014) Orthographic Mapping in the Acquisition of Sight Word Reading, Spelling Memory, and Vocabulary Learning, Scientific Studies of Reading, 18:1, 5-21, DOI: 10.1080/10888438.2013.819356

Ehri, L. C., Deffner, N. D., & Wilce, L. S. (1984). Pictorial mnemonics for phonics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(5), 880–893. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.76.5.880

Fulk, B., Lohman, D., & Belfiore, P. (1997). Effects of integrated picture mnemonics on the letter recognition and letter-sound acquisition of transitional first grade students with special needs. Learning Disability Quarterly, 20, 33-42.

Gaffga, A. J. (2021). Mnemonic Strategies To Teach Letter Formation [Master’s thesis, Wittenberg University]. OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=witt1636709834952114

Galindo, Itzel M., “Effects of bilingual intervention on alphabet knowledge and emergent literacy skills” (2012). Master’s Theses, Capstones, and Projects. 316. (involved Alphafriends)

Golestanirad L, Das S, Schweizer TA, Graham SJ. (2015). A preliminary fMRI study of a novel self-paced written fluency task: observation of left-hemispheric activation, and increased frontal activation in late vs. early task phases. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. Mar 10;9:113. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00113. PMID: 25805984; PMCID: PMC4354285.

Graaff, S., Verhoeven, L., Bosman, A., & Hasselman, F. (2007). Integrated pictorial mnemonics and stimulus fading: teaching kindergartens letter sounds. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(3), 519-539.

Graham, S., Silva, M., & Restrepo, M.A. (2022). Reading intervention research with emergent bilingual students: a meta-analysis, Reading and Writing, 10.1007/s11145-022-10399-8, 36(9), pp. 2433-2464)

Griffith, S. (2016). The efficacy of the Zoo-phonics multisensory language arts program, 6 studies, Sacramento, CA:E3 Research.

Iskur, J. (1975). Establishing letter-sound associations by an object-imaging-projection method. Journal of Learning Disabilities,8(6), 349-353.

James, D. G. H., van Doorn, J., McLeod, S., & Esterman, A. (2008). Patterns of consonant deletion in typically developing children aged 3 to 7 years. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 10(3), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549500701849789

Kim E. DiLorenzo, Carlotta A. Rody, Jessica L. Bucholz & Michael P. Brady (2011) Teaching Letter–Sound Connections With Picture Mnemonics: Itchy’s Alphabet and Early Decoding, Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 55:1, 28-34.

Koka, K. & Zehler, A. M. (2007). Learning to Read Across Languages : Cross-Linguistic Relationships in First- and Second-Language Literacy Development, Routledge, USA: New York. p. 256, chapters :

- Impacts of prior literacy experience on second language learning to read (p. 29).

- Thinking back and looking forward (p. 13).

McNamara, G. (2012). The effectiveness of embedded picture mnemonic alphabet cards on letter recognition and letter sound knowledge. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Rowan University. https://rdw.rowan.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1301&context=etd

Massengill Shaw, D. et Sundberg, M. L. (2008). How a Neurologically Integrated Approach Which Teaches Sound-Symbol Correspondence and Legible Letter Formations Impacts At-Risk First Graders, The Journal of At-Risk Issues, 14(1), pp. 13-21, http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/EJ942830.pdf

Massengill Shaw, D., & Sundberg, M.L. (2008). At-risk preschoolers become beginning readers with neurologically integrated alphabet instruction. Journal of Education Research, 2(1), 61-73.

Massengill, D., Sundberg, M.L., & Stewart, A. (2006). A unique, neurologically integrated approach designed to teach letter sounds and formations. Reading Improvement, 43(3), 111-128. Publisher’s Official Version: . Open Access Version: http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/dspace/

Mesmer, H. A., Kambach, A. (2022). Beyond Labels and Agendas: Research Teachers need to Know about Phonics and Phonological Awareness, The Reading Teacher, 10.1002/trtr.2102, 76(1), pp. 62-72.

Meyer, R. (2022), Promising New Evidence for Improving Alphabet Instruction. Conference handouts from 2022 PaTTAN Literacy Symposium : Bridging Research to Practice.

Molfese, V., Molfese, D. & Prokasky, A. (2016). Identifying Early Literacy Practices That Impact Brain Processing and Behaviour, Perspectives on Language and Literacy, Volume 42, No. 1. (involved Letterland)

Pence Turnbull, K. L., Bowles, R., Skibbe, L. E., Justice, L. & Wiggins, A. (2010). Theoretical Explanations for Preschoolers’ Lowercase Alphabet Knowledge, Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 53(6):1757-68 DOI: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0093)

Piasta, S. B., Hudson, A. K. (2022). Key Knowledge to Support Phonological Awareness and Phonics Instruction, The Reading Teacher, 10.1002/trtr.2093, 76(2), pp. 201-210.

Piasta, S. B., Park, S., Fitzgerald, L., R., & Libnoch, H. A., (2022). Young children’s alphabet learning as a function of instruction and letter difficulty, Learning and Individual Differences, 10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102113, 93, pp. 102113

Piasta, S. B., Logan, J. A. R., Farley, K. S., Strang, T. M., & Justice, L. M. (2021). Profiles and Predictors of Children’s Growth in Alphabet Knowledge. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 27(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2021.1871617

Piasta, S. B., Petscher, Y. & Justice, L. M. (2012). How Many Letters Should Preschoolers in Public Programs Know? The Diagnostic Efficiency of Various Preschool Letter-Naming Benchmarks for Predicting First-Grade Literacy Achievement, Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), pp. 954–958, doi: 10.1037/a0027757

Raschke, D., Alper, S., & Eggders, Elaine. (1999). Recalling alphabet letter names: a mnemonic system to facilitate learning, Preventing School Failure, 43, 80-83.

Roberts, T. A., (2021). Learning Letters: Evidence and Questions From a Science‐of‐Reading Perspective, Reading Research Quarterly, 10.1002/rrq.394, 56(S1), pp. S171-S192.

Roberts, T. A., Vadasy, P. F. & Sanders, E. A., (2019). Preschool Instruction in Letter Names and Sounds: Does Contextualized or Decontextualized Instruction Matter?, Reading Research Quarterly, 10.1002/rrq.284, 55(4) pp. 573-600.

Roberts, T. A., Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2019). Preschoolers’ Alphabet Learning: Cognitive, Teaching Sequence, and English Proficiency Influences. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(3), 413–437. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48558486

Roberts, T. & Sadler, C. D. (2018) Letter sound characters and imaginary narratives: Can they enhance motivation and letter sound learning’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly: Volume 42. Pages 97-111. (involved Letterland)

Roberts, T. A., Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2018). Preschoolers’ alphabet learning: Letter name and sound instruction, cognitive processes, and English proficiency, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 44, pp. 257-274, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.011.

Shanahan, T. (2021). A Question I Hate: Should We Use Pictures (Embedded Mnemonics) When Teaching Phonics?, June 12, 2021, https://www.shanahanonliteracy.com/blog/a-question-i-hate-should-we-use-pictures-embedded-mnemonics-when-teaching-phonics

Shmidman, A., & Ehri, L. (2010) Embedded Picture Mnemonics to Learn Letters. Scientific Studies of Reading, 14:2, 159-182, DOI: 10.1080/10888430903117492

Sener, U., & Belfiore, P. (2005). Mnemonics strategy development: improving alphabetic understanding in Turkish students, at risk for failure in EFL settings, Journal of Behavioral Education, 14(2), 105-115.

Tadiboyina, VR., Deepak, BBVL, & Singh Bisht, D., (2023). Design and evaluation of a gesture interactive alphabet learning digital-game, Education and Information Technologies,

Treiman R, Kessler B, Pollo TC. (2022). Prephonological spelling and its connections with later word reading and spelling performance. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 218, 105359. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2021.105359. Epub 2022 Feb 5. PMID: 35131539. 10.1007/s10639-023-12399-9.

Treiman, R., Kessler, B., Pollo, T.C. (2006)., Learning about the letter name subset of the vocabulary: Evidence from US and Brazilian preschoolers. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2006;27(2):211-227. doi:10.1017/S0142716406060255

Vadasy, P. F., & Sanders, E. A. (2021). Introducing grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs): Exploring rate and complexity in phonics instruction for kindergarteners with limited literacy skills. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 34(1), 109–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-020-10064-y

Ventris Learning, (2022). Embedded Pictograph Mnemonics and the Science of Reading, https://www.ventrislearning.com/wp-content/uploads/Sunform-SoR-White-Paper-2022.pdf

Zhang, L., & Treiman, R. (2020). Preschool Children’s Knowledge of Letter Patterns in Print. Scientific Studies of Reading, 25(5), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2020.1801690